Trigger warning: mental health problems, especially depression.

I am sure at some point in your life you’ve woken up on a Monday morning with a terrible sore throat and a fever. You quickly realize that there is no way you’ll be making it to your 9 am meeting across town, let alone finishing all those reports that are due on Wednesday. You have accepted that you are sick. There is no escaping the 102-temperature glaring red on the thermometer that is sticking out of your mouth. There’s no way to evade all the tissues that are filling your garbage can within throwing distance of your bed.

I am sure at some point in your life you’ve woken up on a Monday morning with a terrible sore throat and a fever. You quickly realize that there is no way you’ll be making it to your 9 am meeting across town, let alone finishing all those reports that are due on Wednesday. You have accepted that you are sick. There is no escaping the 102-temperature glaring red on the thermometer that is sticking out of your mouth. There’s no way to evade all the tissues that are filling your garbage can within throwing distance of your bed.

You reach for the phone and make that call to work: “Sorry, I can’t come in and I will probably not be back for a few days either. I’ve got a nasty flu.” Seems simple enough, right? You are doing a solid to yourself and your co-workers/clients by not coming in and spreading your germs. Plus, you know that taking a few days away from the office is necessary so that you can get back to the job and be more healthy and productive worker rather than pushing through only to end up with something more serious like pneumonia.

But, what if you wake up one morning and instead of having a common cold, you open your eyes and just can’t face your life anymore? You can’t get up and get going. You’re unable to take care of what used to be the “normal” activities of daily living. What if rising from your bed makes you wish you never existed and that the world would be a better place without you in it? How do you call your boss and say, “I can’t come in today because I can’t stop crying?”

This is a difficult and shared reality for so many people. Yet, even though depression, anxiety and other mental health problems exist (and persist), a runny nose and a dry cough usually receive more attention and sympathy in today’s workforce.

May is National Mental Health Month. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that:

May is National Mental Health Month. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that:

“one in four people in the world will be affected by mental or neurological disorders at some point in their lives. Around 450 million people currently suffer from such conditions, placing mental disorders among the leading causes of ill-health and disability worldwide.”

In Canada, it’s not much better:

According to Health Canada, mental health problems are a leading cause of disability in Canada. In 2008, the Institute of Health Economics reported that during any given week approximately 500,000 employed Canadians are unable to work due to mental illness (click here for more details and stats).

Depression, anxiety, and other psychological difficulties afflict millions, and we must at least acknowledge that each and everyday employees are walking into their workplaces silently suffering.

As I explained in a previous two-blog about the differences between Industrial and Organizational (I/O) Psychology versus Clinical Psychology, mental health issues like anxiety and depression are adjacent to but not quite in my immediate wheelhouse.

So how do mental health issues relate to the work that I do? Being heavily involved in HR matters, I have seen first-hand how often mental health issues affect the workplace. For example, when someone is suffering from mental illness, it can hurt their ability to focus and this hurts their productivity and perceived motivation. Some people will need to take time off away from work which can be interpreted as chronic absenteeism. Ongoing absence, a diminished level of concentration, and reduced productivity can all have a negative effect on the bottom line.

Best practices from psychology and the vocational rehabilitation fields suggest that employees who are suffering from mental health problems return to work faster, and generally do better when their employer is committed to some level of accommodation and flexibility. Also, employees who have mental health issues that are diagnosable by a qualified professional, in this case, a registered clinical psychologist or physician, are protected under human rights legislation. In practical terms, this means that employees who disclose the disability of mental health problems are entitled to accommodation unless it brings on undue hardship (more details are available here).

Many people are (wrongly) ashamed of their depression, anxiety and other psychological issues. Sometimes this misplaced and undeserved shame is accompanied by a fear that they will be perceived as weak and unable to do their job well by their fellow co-workers and upper management. This can lead to further distress because that person is also concerned with losing their livelihood too.

Many people are (wrongly) ashamed of their depression, anxiety and other psychological issues. Sometimes this misplaced and undeserved shame is accompanied by a fear that they will be perceived as weak and unable to do their job well by their fellow co-workers and upper management. This can lead to further distress because that person is also concerned with losing their livelihood too.

After speaking with several clients who have kept their depression a secret from their employers, managers, and coworkers, I have come to appreciate that their apprehension about speaking up is often valid. As one client said over the phone recently:

“My boss is the type to ask you how you are doing while rushing past your desk. I don’t think she has ever waited long enough for more than two words to come out of my mouth … so I have just learned to say, “I’m well” … clearly, that’s what she wants to hear or she wouldn’t ask while walking so fast and obviously not very interested.”

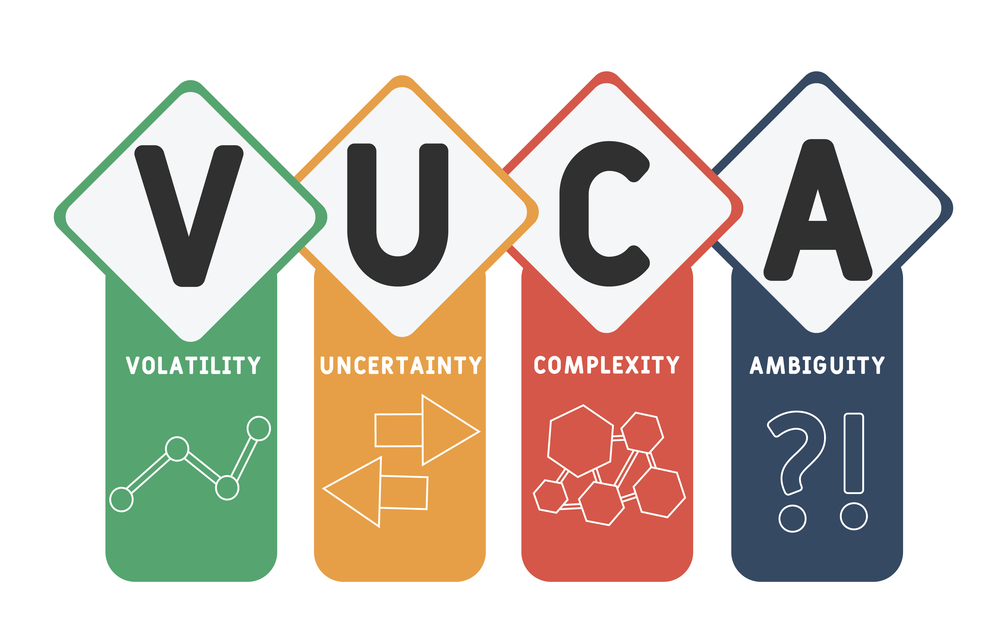

This kind of office atmosphere is not unusual, and in today’s highly competitive, under-resourced, fast-paced world it is no wonder an employee would want to avoid being the squeaky wheel in the company. It doesn’t help that those in upper management positions and high earning executive roles can sometimes be less empathetic by nature (e.g., see this previous article on corporate psychopaths or ‘wolves’ who may even take advantage of others who aren’t at their best).

With all this said, how can employers/organizations do better when it comes to recognizing mental health issues in their work environment? And what can they do (or not do) to avoid making these problems worse?

Some Do’s and Don’ts

Do:

- Make sure policies (if written/formalized) are easily accessible. Make it clearer that sick leave applies to mental and/or physical illness.

- Consider funding or partially funding health care benefits so that employees can get timely access to some counselling services, and other mental health supports either through private service providers or an Employee Assistance Program (EAP). On the surface, this can look expensive, but preventing these problems from escalating is cheaper than chronic absenteeism or presenteeism where someone is at work, but unable to perform well so their productivity is lower than expected.

- If you suspect an employee is struggling with mental health issues be discreet when approaching them so that you can have a private discussion about your concerns towards their well-being. In many cases, it’s best to keep this conversation general (e.g., … I’ve noticed that you haven’t seemed quite like yourself lately. Is there anything that I/we can do to help?). This is especially true if you suspect they are harming themselves (e.g., cutting, using substances, or are expressing suicidal behaviours).

- For more ideas about what employers can do to help support employees who are coping with depression, also consider reading this article.

Don’t:

- Create a strict, unfriendly work environment that is intolerant of employees’ sharing any personal information and/or being able to take time away from work for physical and/or mental health reasons. Given the prevalence of mental health issues, this is a counterproductive approach since WHO notes that approximately 25% of all people will struggle with mental health problems at some point.

- Do not share private information about an employee’s mental or physical health with other staff unless their role is to help resolve and manage the problem (e.g., an HR person with this specific responsibility).

- Don’t claim ignorance, make sure you understand your responsibilities as an employer. A good start is learning more about your duty to accommodate and related policies and procedures suggested by the Human Rights Commissions and organizations with similar mandates.

For more ideas about what you can do to support employees and/or co-workers at work who are coping with mental health problems, read part two of this blog post Mental Health – Making it Work in the Workplace.

Have you ever wished you could get inside the head of a hiring manager? You can. Dr. Helen Ofosu is a Career Coach/Counsellor with a difference. She has worked for organizations to create hiring and screening tools. She’s created countless pre-screening tests, interviews, simulations, and role-plays for organizations of all kinds.

Dr. Helen’s training in Industrial and Organizational (I/O) Psychology means she is a genuine expert in evaluating work-related behaviours. She uses those skills to help hiring managers tell the difference between people who say the right things during interviews and people who actually deliver on the job. In other words, Dr. Helen understands first-hand how job candidates are assessed.

Do you need help navigating the world of work? Contact Dr. Helen today for a free and confidential initial consultation by phone, email, or via direct message on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

More than career coaching, it’s career psychology®.

I/O Advisory Services – Building Resilient Careers and Organizations.™